“Games have this capacity for exploring dynamics and systems that no other form does. This was a story about frustration – in what other form do people complain as much about being frustrated? A video game lets you set up goals for the player and make her fail to achieve them. A reader can’t fail a book. It’s an entirely different level of empathy.” – Anna Anthropy

In its opening level, Dys4ia presents you with an oddly-shaped puzzle piece and a brick wall. There is a hole in the wall with an arrow on the other side; it is obvious that you must get the puzzle piece through the hole. Using your keyboard’s arrow keys, you maneuver the block up to the opening, but a moment’s experimentation reveals that you can’t quite fit; something is wrong. This hole was not built for you. At the bottom of the screen, the game explains: “I feel weird about my body,” before whisking you away.

Dys4ia is an autobiographical game made by Anna Anthropy about her experience with male-to-female hormone replacement therapy. Aesthetically, Dys4ia is simple. The clip-art graphics are pixelated and epileptically bright, and feel comfortable and video-gamey. Sound effects are comprised entirely of silly mouth noises, and the soft, goofy soundtrack by ella guro aka Elizabeth Ryerson (which sounds like a cross between a busy café and the world’s quietest alien invasion) imbues the game with warmth, substance, and whimsicality. But the real success of Dys4ia is how its gameplay masterfully leverages our expectations of what a game should be (and should be about) to thrust us into its creator’s shoes.

Dys4ia is an autobiographical game made by Anna Anthropy about her experience with male-to-female hormone replacement therapy. Aesthetically, Dys4ia is simple. The clip-art graphics are pixelated and epileptically bright, and feel comfortable and video-gamey. Sound effects are comprised entirely of silly mouth noises, and the soft, goofy soundtrack by ella guro aka Elizabeth Ryerson (which sounds like a cross between a busy café and the world’s quietest alien invasion) imbues the game with warmth, substance, and whimsicality. But the real success of Dys4ia is how its gameplay masterfully leverages our expectations of what a game should be (and should be about) to thrust us into its creator’s shoes.

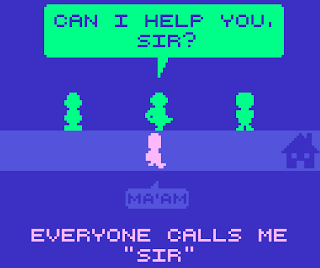

The story is told in a sequence of fast-paced interactive vignettes, each accompanied with a storybook-style narration. Each one involves the player using the four arrow keys to control some action in the scene. Some scenes are literal; some scenes are more abstract and metaphorical. You guide your character past onlookers who mistakenly call you “sir”. You pop estrogen pills. You answer your cellphone; your sister wants to know why you’re taking hormones. You binge on chocolate and pizza. You hold hands with your girlfriend.

This frenetic, channel-switching structure lets Dys4ia communicate a wide range of experiences, by presenting them as simple mini-games. When combined with the concise, intimate writing, the gameplay communicates a powerful sense of emotion.

In his review of Dys4ia for Penny Arcade, Ben Kuchera interviews Anthropy and discusses the controversy around calling it a game. He leaves his conclusion open, but touches upon the point that discussion of “is it a game” often tends to be circular, exclusionary, and highly subjective. It makes perfect and logical sense for this reaction to happen; when an audience comes into contact with a work that challenges something they have become acclimated to, there is a tendency to discredit it. It’s easy to see how some gamers would go into Dys4ia expecting a game and instead feeling tricked into listening somebody else’s politics. Kuchera also talks to Anthropy about the choice to release Dys4ia on Newgrounds, a mainstream gaming website that could be described as very traditional. On Newgrounds, Dys4ia received a lot of attention from people who wouldn’t otherwise come in contact with the issues it raised, and it caused quite a stir of controversy in the comments thread (the game has almost 800 user reviews and counting, with an average user score of 4 / 5 ).

Dys4ia pushes boundaries. Its subject matter deals with a controversial subject that is extremely difficult for most people to relate to. When considering the audience of people who play a lot of video games, it becomes an even more unlikely matter. But elegantly tackling the issue of gender dysphoria is not its most radical trait.

The conventions that define most modern videogames describe an experience very different to Dys4ia. Most games revolve around meaningful player choice, usually in the form of a central mechanic that requires some skill or strategy to master. As the player becomes better and better at this mechanic, the game rewards them by unlocking more story, missions, or even new mechanics or abilities. If the player fails to learn the mechanic, they will be unable to progress until their skill improves sufficiently. Almost all successful games follow this format. For an example, let’s look at the 2011 indie game Bastion, developed by Supergiant Games, which has sold upwards of 2 million copies on several platforms and enjoyed critical acclaim.

In Bastion, players control the main character (simply referred to as “the Kid”) as he fights his way through the remnants of his homeland after a mysterious event called “the calamity.” The whole game uses a tilted top-down camera view, showing the Kid, his immediate surroundings, and any enemies nearby. The player can move the Kid, aim and use his weapon, and use any of a set of secret skills. Touching enemies will lower the Kid’s health. If the Kid’s health falls too low, he will lose a life and be set back. If the Kid loses too many lives, the player will have to restart a larger chapter of the game. As the game progresses and the events of the plot unfold, players fight different enemies and unlock different weapons to use. Each type of enemy requires strategy to defeat, and each weapon has different strengths and weaknesses. The game uses these simple building blocks to challenge and reward the player throughout the game.

Bastion offers the players lots of meaningful choice, both in narrative and in gameplay. Before setting out on each mission, the player chooses 2 weapons (each level unlocks a new one to select from) and one secret skill to take with them (these range from weapon-specific enhancements to random skills such as a decoy to distract enemies’ attention). Players can also drink spirits (that they unlock as the game progresses) that give passive bonuses during missions, such as Dreadrum (increases the chance of critical hit attacks) and Stabsinthe (the Kid automatically retaliates when hit by an enemy). Even the game’s ending forces the player to make a handful of tricky moral choices.

Dys4ia eschews this structure entirely. It involves no strategy and no meaningful choice. If the player gets stuck anywhere, the game simply moves on with little regard. There is exactly one way to get through the game, there is exactly one ending. There isn’t even a central mechanic; every vignette is a game unto itself, with new rules to learn and new mechanics to master. This is what makes Dys4ia really interesting. If it has no reward schedule, no strategy, no challenge, no player choice, how is it so compelling? I believe it’s because Dys4ia capitalizes on the strongest power of games– empathy.

When a player takes control of a video game character, a special and almost unreasonably strong bond of empathy forms. Much like an actor in a play (to use Anna Anthropy’s own analogy), you are thrust into a role and expected to play along. This ends up being powerfully engaging; a good game pulls the player to keep acting. The events of the game don’t happen to some character in a book or on a screen; they happen to you. It’s one thing to read, “I feel like a spy whenever I use the women’s bathroom;” it’s another thing entirely to sneak through the stalls yourself, dodging watchful restroom-goers on your way to the toilet. In this manner Dys4ia takes the best elements of the best games, and runs in a completely different and wonderful direction.

Leave a Reply